Source: National Geographic

Old U.S. coal-fired power plants, the target of new anti-pollution rules, aren’t necessarily shutting down. Many are getting a second life as they’re “repowered” with natural gas.

Decisions to keep running these plants—which are often more than 40 years old—have sparked court battles in New York and are raising questions about how much should be done to retain legacy fossil-fuel facilities.

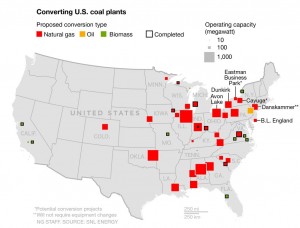

In the past four years, at least 29 coal units in 10 states have switched to natural gas or biomass, according to SNL Financial, a market data firm. Another 54 units, mostly in the U.S. Northeast and Midwest, are slated to be converted over the next nine years. The future and completed conversions represent more than 12,000 megawatts of power capacity, enough to power all the homes in New England for one year.

By switching to natural gas, plant operators can take advantage of a relatively cheap and plentiful U.S. supply. The change can also help them meet proposed federal rules to limit heat-trapping carbon dioxide emissions from power plants, given that electricity generation from natural gas emits about half as much carbon as electricity from coal does. (Vote and comment: “Can Natural Gas Be a Bridge to Clean Energy?”)

Battles in New York

In New York, at least three large coal pla nts that faced closure are slated for conversion to natural gas—if courts allow it. The Dunkirk plant in western New York is the focus of a lawsuit by environmental groups that say the $150 million repowering will force the state’s energy consumers to pay for an unnecessary facility.

nts that faced closure are slated for conversion to natural gas—if courts allow it. The Dunkirk plant in western New York is the focus of a lawsuit by environmental groups that say the $150 million repowering will force the state’s energy consumers to pay for an unnecessary facility.

“What we’re concerned about is that the Dunkirk proceeding is setting a really, really bad precedent where we’re going to keep these old, outdated, polluting plants on life support for political reasons,” said Christopher Amato, a staff attorney at Earthjustice, an environmental group, and a plaintiff in the case.

Dunkirk’s operator, NRG, wanted to mothball the plant in 2012, saying it was not economical to run. The utility, National Grid, said shutting it down could make local power supplies less reliable, a problem that could be fixed by boosting transmission capacity—at a lower cost than repowering Dunkirk. Earthjustice alleges that the deal to reopen the plant, which New York Governor Andrew Cuomo announced last December, was a purely political move meant to preserve jobs and local tax revenue.

National Grid spokesperson Steve Brady, while confirming that transmission upgrades could have addressed the reliability concerns, echoed the idea that local incentives were behind the Dunkirk decision. “There was more at stake with regard to potential plant closure than just reliability,” he said. “Local and regional economic issues—including construction and permanent jobs, property taxes, other economic impacts, and so on—were also important to the evaluation process directed by our state regulatory agency.”

Environmental groups also object to Dunkirk’s ability to burn both coal and natural gas, potentially allowing it to revert back to the dirtier fuel if natural gas prices rise. But David Gaier, an NRG spokesperson, said that converting the plant to gas requires staffing and equipment changes that cannot be easily reversed. “It’s not like you can switch back and forth. That’s simply not possible,” he said. “You’d have to, in a sense, convert back to using coal.”

Another lawsuit in New York, filed by the environmental organization Riverkeeper, targets the repowering of the Danskammer facility in the southeastern part of the state. That coal plant suffered flooding damage during Hurricane Sandy in 2012 and was slated for demolition until new regulations made it feasible to bring the plant back online. Riverkeeper, concerned about the plant’s potential effects on wildlife in the adjacent Hudson River, contends that the project should have triggered a more comprehensive environmental review than it did.

Two other coal plants, the mid-state Cayuga station and a smaller industrial power facility at the Eastman Business Park in Rochester, also are slated to be repowered with natural gas. Earthjustice is fighting the Cayuga proposal along with Dunkirk, saying the state’s plan “would lock the region into continued use of fossil fuels and hike electricity bills.”

A Need for More Pipelines

Elsewhere in the country, coal repowering projects have met with mixed reaction. In Indianapolis, environmentalists hailed the decision this summer to convert its Harding Street power plant from coal to natural gas as a “clean air victory.” For many towns, converting an old coal plant means saving jobs and tax revenue that would otherwise disappear.

Still, such conversions often entail job cuts, because fewer employees are needed to run natural gas plants. Some projects also encounter resistance because of the new pipelines they require.

The Sierra Club is fighting a proposed conversion of the B.L. England power station in New Jersey, for example, because it would need to be served by a new pipeline running through the Pinelands National Reserve. For the proposed Avon Lake project in Ohio, NRG is tasked with persuading landowners to allow construction of a necessary pipeline.

While conversion advocates say natural gas is a “bridge” fuel that buys time for a transition to clean energy, others argue its use is hindering renewables by delaying them. Many of the planned repowering projects will extend the already long service of fossil-fuel facilities. (Related: “Switch to Natural Gas Won’t Reduce Carbon Emissions Much, Study Finds.”)

“Do you pump a whole bunch of the public’s money into outdated, inefficient infrastructure, or do you say it’s time to move forward and invest in renewable energy and upgraded transmission to move that renewable energy around?” said Kim Teplitsky, deputy secretary of the Northeast Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal campaign. Teplitsky’s group is opposed to the revivals of New York’s Dunkirk, Danskammer, and Cayuga power plants.

Power providers and regulators, on the other hand, point to the need for reliability, especially in extreme weather conditions. “The system requires a certain amount of megawatts and a certain amount of reserve margin to ensure that the system will be stable and reliable at all times,” said Gaier of NRG, which operates both renewable and fossil-fuel units. “The number of megawatts is simply not replaceable in the short term with renewables.”